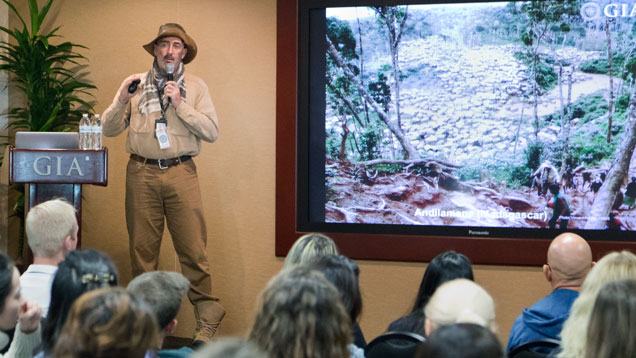

Pardieu Brings Ruby Rush to Life with Stories, Updates from Madagascar

March 10, 2016

A gem “fingerprint.”

That’s what Vincent Pardieu, senior manager of field gemology for GIA in Bangkok, and his six-person team are looking for as they traverse the globe – and log hours in the lab – finding, analyzing and cataloging colored stones for GIA’s Colored Stone Identification and Origin Report reference collection.

So when Pardieu’s team learned of a newly discovered ruby deposit in northeast Madagascar in July 2015, they arranged a field expedition and set to work investigating and documenting the rubies of the island nation’s Zahamena National Park. On Nov. 4, just a month after their trip, Pardieu and field assistant Manuel Diaz visited GIA’s Carlsbad campus to share their findings − and sometimes harrowing experiences − with students and staff.

“To have a reference collection, you need to build it. And the best way to build it … is to send somebody to the field – to go and visit every gem mine that is known, and collect samples,” Pardieu said.

Pardieu, a GIA Graduate Gemologist with a long career as a gemological researcher, tour guide and gemology writer, said that prior to recent discoveries, Madagascar was known primarily for its active sapphire mines.“The two most powerful tools we have in the lab to identify if a stone is coming from this place or that place are its inclusions and trace element chemistry. But if a stone is clean (or heated), inclusions are useless … so chemistry is more powerful than inclusions because we can get chemical data from a gem any time.”

A 2000 discovery “deep in the rainforest” of the eastern Andilamena district “put Madagascar on the map for rubies,” Pardieu said. And though miners carried bags brimming with the stones (“I never saw a place with so many rubies,” he said), most of them were too heavily fractured for use in jewelry without treatment. The deposit really started to be active after the discovery of the lead glass treatment in 2004. The area became known for the stones’ low quality until a 2012 discovery of sapphire and ruby near the small, remote village called Didy.

Didy’s stones were comparatively clean, beautiful and big (“I heard about rubies over 20 carats,” Pardieu said). A gem rush occurred, but mining was stopped within a few months because, unlike the previous deposit near Andilamena, that deposit was located in a protected area near three national parks.

“If the discovery was noticed by the gem trade, due to the quality of the stones produced, it was also noticed by conservation groups, who began to be very concerned about gem mining in protected areas in that country,” Pardieu said.

“We had to walk for five days in the jungle – walk, sleep and eat in the jungle – in order to reach the area with miners,” Pardieu said. “And we had to take security with us because we were informed that a lot of bandits were active in the area. If you go there as a foreigner without anybody, you will probably get attacked on the road. In many new mining areas, it’s like the Wild, Wild West.”

Once they finally arrived at the site, they discovered it was inside the Zahamena National Park, where mining is illegal. They witnessed between 500 and 1,000 informal miners working the deposit with hand tools. The arrival of such a large number of people inside the park was obviously a serious problem for people in charge of conservation in Madagascar, Pardieu said.

“It’s very important to (conservation groups) to keep places like Zahamena safe, especially [because] you don’t have a lot of forests left,” he said. "Less than 5 percent of the island still has forests, and they are very unique because the type of plants and animals there are found nowhere else on the earth.”

Most of the samples they saw were dark and quite opaque.

“You had also some stones that were nice-looking, with bright colors, and some of them were really nice,” he said. “This is a small minority – probably less than 1 percent of the production in the area, but for the informal miners it was worth the effort to come to such remote place as prices given by foreign merchants in town were attractive. We heard about some stones that were clean and over 10 carats. That is the type of stone that might one day be submitted to GIA, so we have to be able to get the reference samples because we need to be able to recognize them in the future.”

With the help of a local licensed gem merchant, the GIA team was able to acquire a range of samples from the informal miners. Back in Bangkok, they wasted no time and started to work on the samples: taking photos, cataloging them and collecting data.

They began then their search for the Zahamena rubies’ gem fingerprints.

“The two most powerful tools we have in the lab to identify if a stone is coming from this place or that place are its inclusions and trace element chemistry,” Pardieu said. “But if a stone is clean (or heated), inclusions are useless … so chemistry is more powerful than inclusions because we can get chemical data from a gem any time.”

“Nevertheless, the best way is when you have the combination of all the techniques, when you get the same result with inclusions, chemistry and spectroscopy. When everything is pointing in one direction, then you can feel quite confident about the origin of the stone,” he said.

Pardieu said that after a 15-sample analysis of the common inclusions (including unhealed fractures; long, thin silk; zircon crystals; rutile and apatite) and trace element chemistry, he was optimistic about the GIA laboratory’s ability to determine the rubies’ origin should they show up in the lab down the road.

The inclusions were “quite characteristic” of the deposit, he said. “Rubies from the Zahamena region will be in a very good position to be identified.”

Pardieu said that he sees a host of challenges and opportunities for gem mining in Africa.

“One of the questions the trade has to think about is ‘Should people just go mine everywhere?’ Obviously, the trade would benefit by promoting responsible business practices.

“There is a huge potential to associate gems – and the gemstone business – with the good guys,” he said, citing examples of companies that employ transparency efforts and finance conservation efforts.

“But the danger is that if the trade does nothing, and if illegal mining threatens places like National Parks it will be associated with the bad ones … and that would not be a good thing for our industry as we need more friends than enemies,” he said. “As a field gemologist visiting the places where gems are mined, it is quite obvious to us that what happens where the stones are mined also become important. We believe it is our duty to pass that message along − as equally important as it is to bring back samples to be able to identify the gems from this source.”

Jaime Kautsky, a contributing writer, is a GIA Diamonds Graduate and GIA Accredited Jewelry Professional and was an associate editor of The Loupe magazine.