Montana Yogo Sapphires’ Unique Gemology

April 19, 2019

Despite its Atlantic-to-Pacific land mass, the United States never has been known as a major source for gemstones. The one exception has been sapphire, though the story of Montana sapphires always has been obscured by more exotic locations.

Montana has been an important source of blue sapphire off and on since the 1890s and have unique gemological properties that distinguish them from those mined in other locations around the world, including Kashmir, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Australia. GIA researchers Nathan D. Renfro, Aaron C. Palke, along with Richard B. Berg of the Montana Bureau of Mines, conducted an extensive analysis of gems from the Yogo Gulch deposit, reporting their findings in Gems & Gemology’s Summer 2018 issue.

Yogo sapphires’ chief trait is that many of them have an attractive violet to blue color coming out of the ground and are generally not heat treated – the gem-quality stones rarely, if ever, respond to treatments. In addition, the color is generally evenly spread throughout the stones, so they lack the zoning that can be common in sapphires from other locales. Unfortunately, nearly all of the rough crystals are flat, tabular pieces that can only be cut into small gems. Thus, carat-plus sapphires from this source are quite rare.

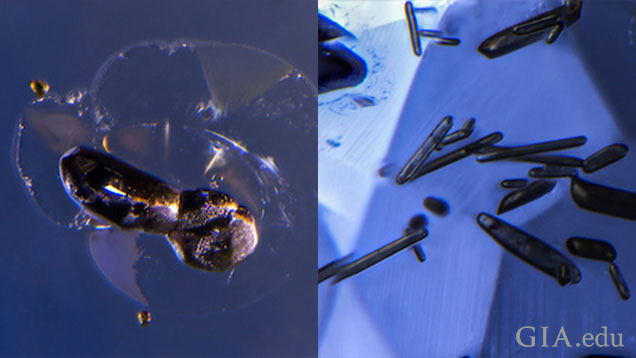

Deeper gemological examination found that Yogo stones are unique in other ways as well. Most blue sapphires contain tiny needle-like or “silk” rutile inclusions. In the case of the classic Kashmir stones, for example, the clusters of near microscopic rutile impart a velvety glow to the gem, making them highly prized, with price premiums to match, for more than a century. This silk also can be a distracting clarity characteristic of some sapphires at times and heat treatment is relied upon to improve their clarity and color. On the other hand, Yogo sapphires rarely contain fine, needle-like rutile silk which was found in only one of the samples examined.

Inclusions are often the most tell-tale signatures of a gem’s origin and Yogo’s primary signs are stress halos that surround very small pieces of other minerals trapped inside the still-forming sapphire. The halos (also called decrepitation halos) were formed when the mineral inclusions expanded inside the sapphire during its formation and caused tiny stress fractures. Other common, but distinctive inclusions are negative crystals – very small hollow areas filled with other materials.

Even deeper examination found that Yogo sapphires have a distinct trace element signatures with specific values of manganese, chromium, titanium, iron and gallium that are different from other sapphires.

While Yogo sapphires, and most other sapphires emanating from Montana, have an attractive natural blue color that commands premium prices, their small sizes and the complexities of working the deposits made it economically difficult to mine them.

The first Yogo source was discovered in 1895 and by the turn of the century, production averaged 400,000 carats a year. About 25% were gem quality and the remainder industrial goods used in watch movements and abrasives. This mine, sometimes referred to as the English Mine, operated until 1929. In 1910, it yielded the largest sapphire ever found in that locale, a 19 ct rough that was cut into four gems, the largest 8.5 cts.

The mine site is located within a long dike (a geological formation of volcanic rock layered above older, pre-existing rock) that held other sapphire deposits. Three other mines went into operation but, by the late 1920s, competition from synthetic sapphires for watch movements and abrasives, coupled with a disastrous flood and declining yields, made mining unprofitable.

The area remained abandoned for nearly 30 years before a group of investors renewed mining activities in 1956, but were unsuccessful. Several other failed attempts to revive mining at Yogo Gulch were made until 1980, when a mining engineer named Harry Bullock acquired the mining operations for $6 million and set out on a well-publicized effort to mine and market “Royal American Sapphires” under the corporate name Intergem. After some initial success, competition from inexpensive heat-treated Sri Lankan sapphires, mounting debts and increased mining costs sank the venture in 1985.

That year, prospectors found a new deposit in the southwestern tip of the dike. They called it the Vortex Mine and produced about 45,000 carats of cuttable rough a year, but closed in 2004. The following year, a miner named Mike Roberts took a part ownership of Vortex and successfully mined it on a small scale until he was killed in a mine site accident in 2012.

New owners are trying yet again to resume mining the Yogo Gulch and have been working on making necessary improvements to bring the mine back into production.

This research project, Renfo and Palke noted, “was a few years in the making.” One motivating factor for the study was the demand for Yogo origin, instead of the more general USA (Montana) notation on GIA lab reports.

A second factor, Renfro said, was that there was a “hole in the literature. Previous publications generally focused only on the geology (of the Yogo area), but there was no thorough gemological characterization of the material.”

And a third motivation was, “I just like Yogo sapphires,” he said.

Nathan Renfro completed his undergraduate studies in geology in 2006 and enrolled in GIA’s resident Graduate Gemologist (GG) program as a recipient of the William Goldberg Diamond Corporation scholarship. Renfro also completed his FGA in 2014. After finishing the GG program, he was hired by the GIA laboratory as a diamond grader and soon transferred to the Gem Identification department in 2008. Since then, Renfro has authored or co-authored more than 100 gemological articles and lectured to several gem and mineral groups throughout the U.S. His primary areas of gemological interest are inclusion identification and photomicrography, gemstone cutting and defect chemistry of corundum. Renfro is manager of the Gem Identification department and also is a microscopist in the Inclusion Research department. He is also the editor of the “Microworld” column in Gems & Gemology and a member of the editorial review board.

Dr. Aaron Palke started his career in gemology as a postdoctoral research associate at GIA after earning his Ph.D. in Geology from Stanford University. During this time, Palke investigated the geological history of rubies and sapphires by studying minute inclusions in these precious gems. A senior research scientist at GIA, he helps lead colored stone research efforts in order to provide more reliable country of origin determinations and treatment identification for rubies, sapphire, emeralds and other colored stones. See Palke's profiles on ResearchGate and Google Scholar.

Russell Shor is senior industry analyst at GIA in Carlsbad.