Making the Cut: The Art and Science of Fantasy Carving

January 10, 2020

Some gem cutters are “gem whisperers” who claim their rough “tells” them what it wants to become. For them, carving becomes a process of communication with the material, closely observing and taking note as the rough’s inner structure and features guide the design. Others take a mathematical approach to cutting the rough and achieve stunning, precision faceting.

No matter the method, these incredibly gifted artists create breathtaking jewels.

About the Science

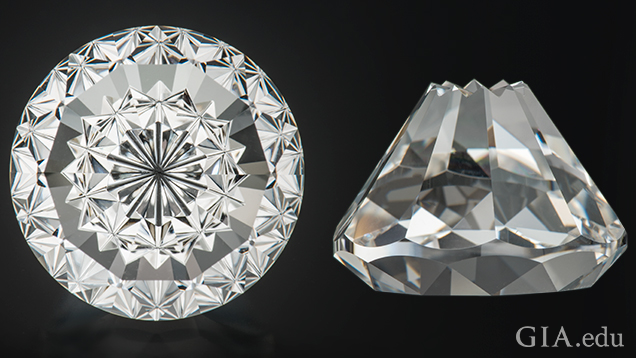

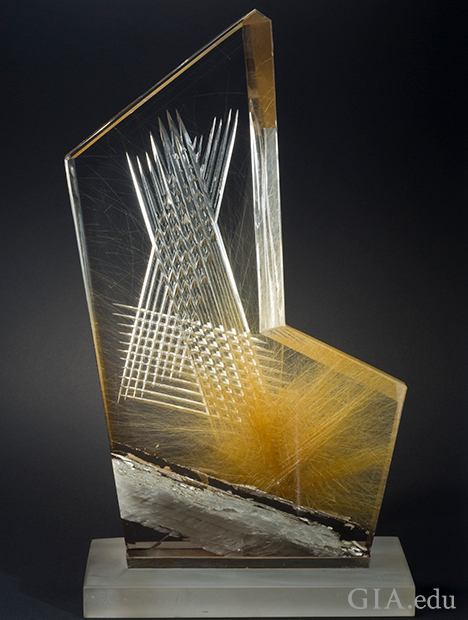

Flat facets are the traditional two-dimensional facets we see in diamonds and colored gemstones. They are shaped by the adjoining facets and the angles at which they intersect. Concave facets, on the other hand, literally add another dimension to faceting. They not only possess length and width, but also depth. Their potential to create sculptural works of art is endless.

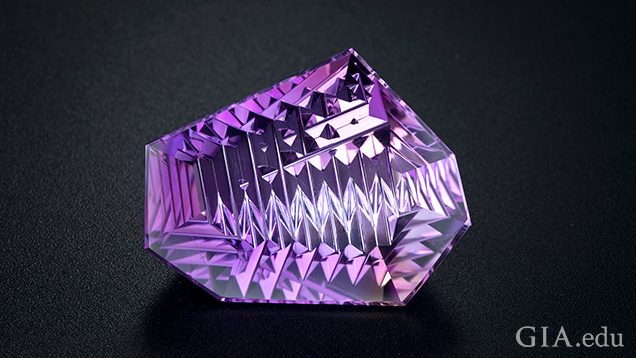

Many people feel that concave facets increase the stone’s brilliance and scintillation, giving it more life and beauty. A wide reflection of bright light from a flat facet washes out color. A concave facet acts as an internal convex mirror to produce reflected rays from more directions within a gemstone. The light from above reflects to the overhead observer as a narrow bright line of light at the top of the curved surface, and each side of the line will be darker, setting up strong contrast.

“Strong contrast makes a gemstone appear brighter and more appealing ... Scintillation is more dynamic when there is strong contrast between adjacent virtual facets,” according to Al Gilbertson, a research associate at GIA, in a 2013 Gems & Gemology article.

The internal reflections of light tend to hide inclusions and also eliminate windowing. Gems with light to medium tones show the greatest improvement in appearance. Dark stones may look darker. Multi-color ametrine, tourmaline and sunstone make especially attractive carvings and rutile inclusions in quartz add special interest.

“This brilliance [from scintillation] can give the impression that the stone has a higher refractive index (RI), making quartz look like beryl, beryl like topaz, topaz like corundum, and corundum like zirconium,” according to Eddy Vleeschdrager in “Cutting Technique Flat, Concave, or Convex?” a 2002 article in Le Bijoutier International.

Craftsmen in the Idar-Oberstein area have produced stones with concave cut facets on the pavilion since the early 1900s. These stones became fashionable around 1920, and again in the 1950s and ‘60s.

About the Artists

Sherris Cottier-Shanks tells us the material talks to her. She senses its energy and gets a picture in her mind that she translates into the beauty of its new form. Using a simple carving arbor, she holds the gem by hand as it is being carved, resulting in curved form with a very soft, liquid appearance. She gained inspiration from Henry Hunt and indigenous Canadian Inuit art.

Michael Dyber became the first American to ever win first prize in competitive gem design at the annual German Award for Jewelry and Precious Stones in Idar-Oberstein, 1994. He is known for his signature, trademarked “Dyber Optic Dishes” and “Luminaires.” Both techniques create optical illusions using a form of concave faceting. The “Luminaires” constitute a hollow channel form of faceting within the gem.

John Dyer began a meteoric gem cutting career in 1996 when his trial and error methods began to yield beautiful, sparkling gemstones. He won his first AGTA Cutting Edge Award in 2002 and in 2005 was the first person to sweep an entire category in the AGTA Cutting Edge Awards. He creates collections of trademarked cuts that live up to their names: “Dreamscape,” “Starbrite,” “Sunburst,” “Regal Radiant,” “Light Weaver” and “Sculptural.”

Mark Gronlund, an award-winning cutter himself, met with Richard Homer early in his career, and became intrigued by the concave and convex facets created by the OMF (optically magnified facet) cutting machine. His fascination with curved lines led him to create a niche in non-traditional spiral and scallop cuts. He creates gemstone suites of bold colors and shapes for designer jewelry.

Dalan Hargrave’s focus is in developing new gemstone cuts as works of art. He teaches classes in the lapidary arts as a way of passing on his knowledge to the next generation of artisans. He enjoys customizing specialized faceting equipment for his innovative styles.

Richard Homer is known for the exceptional brilliance of his cut gems. He masterfully curves the facets along the table, pavilion and girdle that return an explosion of light and color, and is often credited with designing the innovative “concave facet.” His dramatic designs sometimes employ new cutting techniques and curved outlines for which he custom tools specialized equipment.

Alexander Kreis, of KREIS Jewellery, hails from a long line of lapidaries based in Idar-Oberstein. He challenges himself to create gem sculptures that tell a story. He creates innovative techniques and tools when necessary for the design and concept.

Bernd Munsteiner is often credited with inventing the fantasy cut, which employs the art of sharp, angular cutting or faceting to reflect and refract light in transparent gems. He began his work in agate relief before moving on to transparent materials in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, removing large areas of the material for the sake of his art, defying the conventional practice of cutting to retain weight. The results are dynamic sculptural pieces that create movement of light comparable to animation. He is known for bold notches or slashes, producing a striking geometric form.

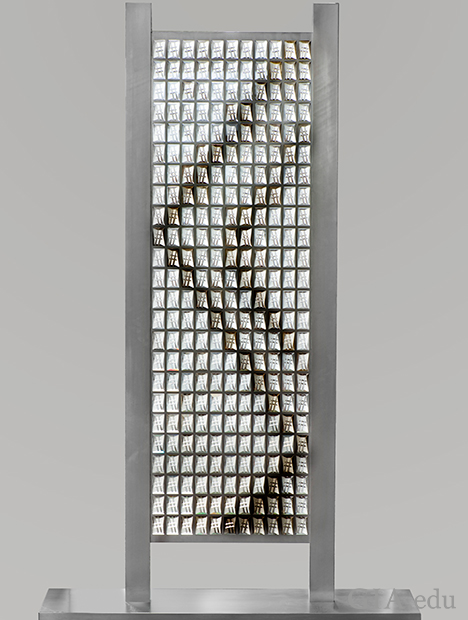

Tom Munsteiner carries on his father's legacy as a master of gem sculpture. His work reflects the influence of architectural elements in his designs, such as his “Visions in Crystal” sculpture, which stands at more than 6 feet tall and is comprised of 264 tiles of rock crystal quartz, citrine and smoky quartz each cut with various angular facets. He created the piece as an example of how gemstones can be seen as fine art.

Further Reading

Morgan, A. D. (October 2002) Development of concave faceting of gemstones, The Journal of Gemmology, October 2002.

Munsteiner, Bernd, Reflections in Stone, Wilhelm Lindemann, editor. 2004, Arnoldsche.

Oriel, Andy, (November 1997) Learning Curve, Lapidary Journal.

Weldon, Robert, (April 2005) Mathematical Brilliance, Professional Jeweler.

Sharon Bohannon, a media editor who researches, catalogs and documents photos, is a GIA GG™ and GIA AJP®. She works in the Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center.