Lightning Ridge: The World Capital of Fine Black Opal

September 16, 2016

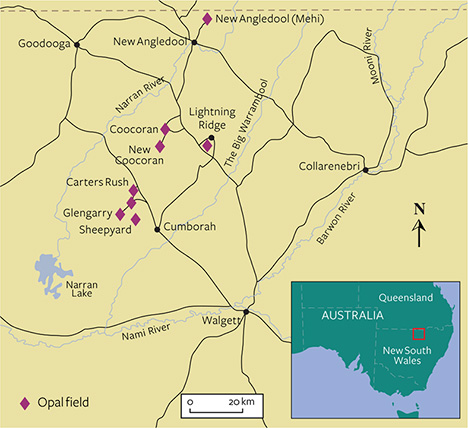

The town of Lightning Ridge, in central northern New South Wales, is widely considered the main source of high-quality black opal. A group of field gemologists from GIA visited Lightning Ridge and the area mines in June 2015. A documentary has been created from this visit.

The World Capital of Black Opal

HISTORY

Opal was discovered in Lightning Ridge in the late 1880s, but its value was not recognized until Charlie Nettleton sank the first shaft in 1903 and sold the first parcel of black opal later that year. The town dramatically expanded with the influx of miners from White Cliff, another world-famous opal mining area in Australia. By 1909–1910, when the local population rose to around 1,000, mining operations had expanded to about 10 km west of the town. The moderate production of opal was quite stable between 1910 and 1920. After 1920 the mining fields were very quiet, with little production recorded.

town is quite small, but opal mines are distributed all over the town and its surrounding areas.

The reactivation of opal production happened in 1958 with increasing demand and the introduction of machinery mining. The increasing price of black opal not only further expanded underground mining but also made large-scale open-pit mining possible around 1970. The heyday of black opal came in the 1980s and 1990s, when the Japanese fell in love with the gem. As the demand from Japan started to fall, the Chinese gradually learned more and more about opal, and China has the potential to become a major opal consumer.

DEPOSIT AND MINING

In addition to the mines within 10 km of Lightning Ridge, opal is mined in the town’s outlying fields. Opal is recovered from the claystone, siltstone, or clayish sandstone layers and lenses of Early Cretaceous age. Locally opal tends to form close to the boundary between the Wallangulla Sandstone and Finch Claystone units. The depth of the deposit is usually less than 30 meters.

Occurring mainly as nodules, opal is also found as seams in the outlying fields. Occasionally opal is found as rare opalized fossils of Cretaceous age. The black seam opal is mined in the outlying opal fields such as Grawin, Glengarry, Sheepyard, and Carters Rush. The underground mines in these fields are quite sturdy. The sandstone roofs are stronger than those of the Lightning Ridge mines. According to one mine owner, the occurrence of black seam opal is highly controlled by local structures that local miners call “blows.” Blows are vertical zones of crushed and broken rock; the geological name is breccia. Although there has been much research and many hypotheses about the timing and mechanism of opal formation, the topic is still highly debatable.

Opal mining in Lightning Ridge usually begins underground instead of in an open pit. The mine becomes an open pit only when the price of the stone makes this change profitable. A special digger has been developed for opal mining in the clay-rich layers. Even though they are all in the same region, opal mines in the town’s vicinity and those in the outlying area are still quite different. After extraction the material is sucked up to the surface by a strong “blower.” Then it is transported to the washing plant for processing. An agitator made from a converted concrete mixer is used to wash opal-bearing clays. Water is pumped into the revolving barrel and breaks down the claystone without damaging the opal. After about a week of washing, the sludge flows to the sorting table for harvesting. Water is one critical problem that many mining towns face, including Lightning Ridge. Locals informed us that it had been very dry for several years in a row and a water shortage had negatively influenced processing.

The team visited a prospecting site north of Lightning Ridge. Auger drilling is applied to sample the stratigraphy, and the depth of the possible opal-bearing layer is recorded for future reference. The claystone layer pulled up by the auger is processed on-site to estimate the opal concentration.

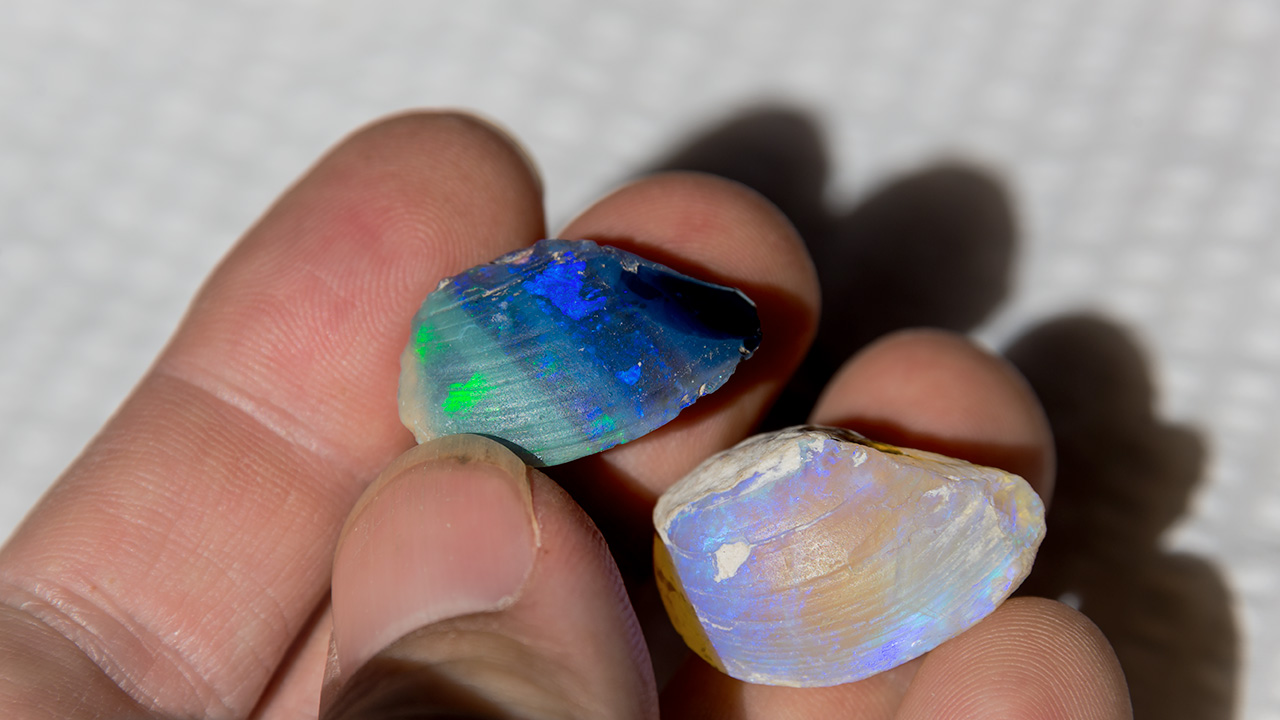

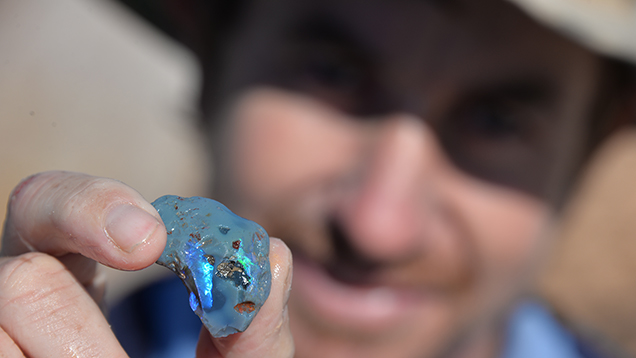

The GIA team collected both “A-type” and “B-type” black opal samples in Lightning Ridge. The A-type samples were found in Frederic Mallock’s underground mine and extracted by GIA field gemologist Vincent Pardieu. Some samples were collected at the washing plant as well. All samples will go to GIA’s collection.

FROM MINE TO MARKET

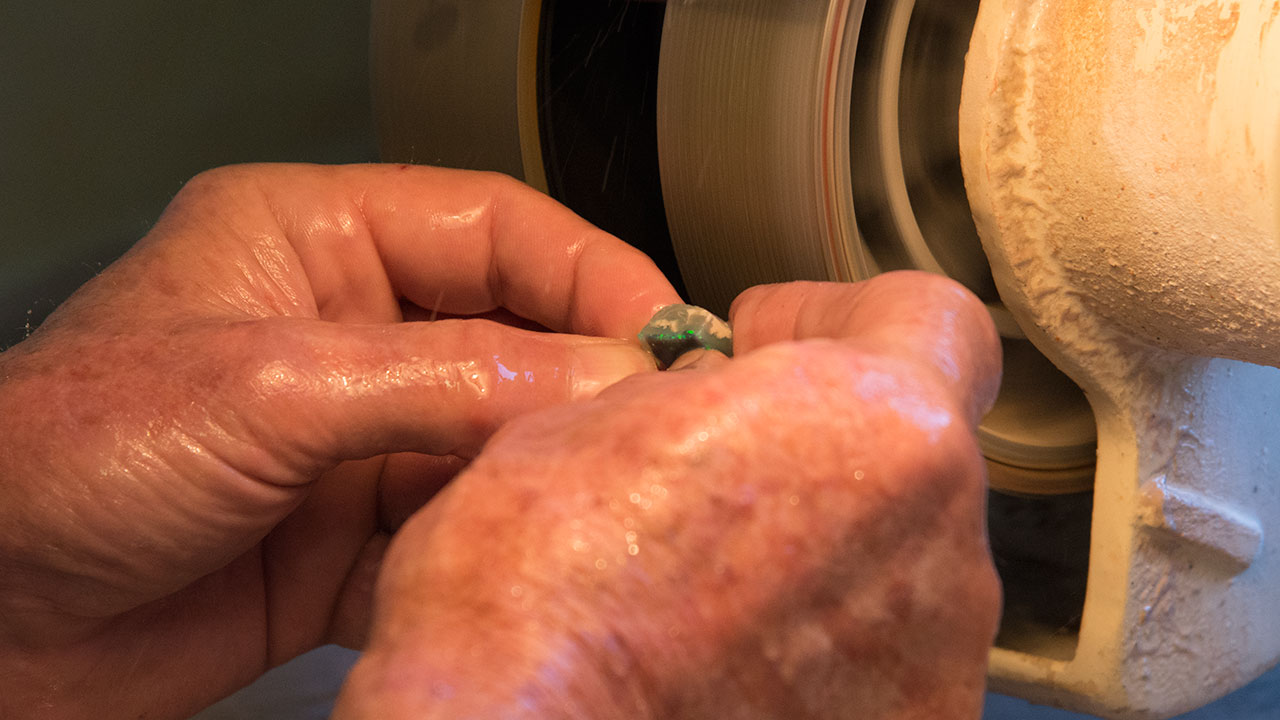

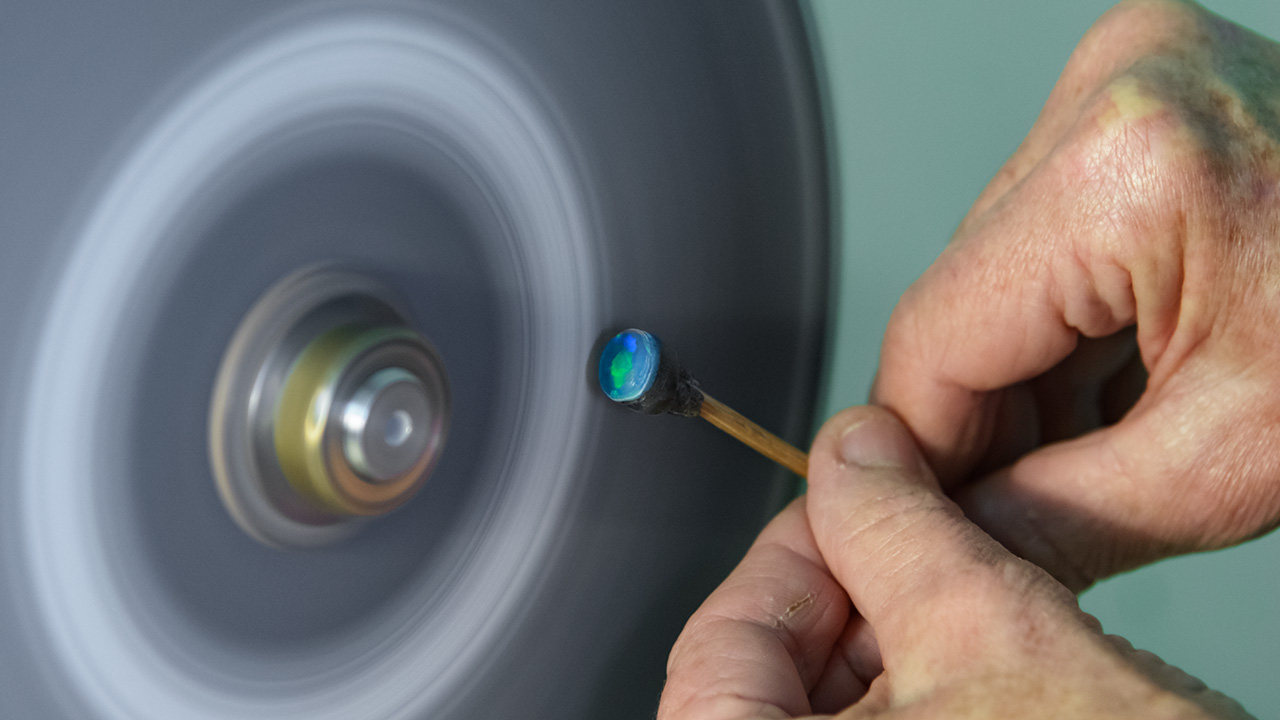

We saw that the whole chain from mine to market has been developed in Lightning Ridge. The best rough from the mines is kept in town for polishing. Experienced opal cutter Jerry and his wife, Helen, guided us through the polishing process. They have been polishing opals for over 25 years and have finished many spectacular stones for world-class jewelry brands, such as Cartier.

Polished cabochons are the most common finished opal. Opals are also carved into different shapes based on their form and color. This is very similar to jade carving in China. The medium- to lower-quality material is better used in this case, and the weight retention is higher as well. Carving is done in Lightning Ridge, but some dealers transport the material to Southeast Asia for this purpose.

Visitors can find many opal jewelry stores on Lightning Ridge’s main street. You will often find that the store owner is also a miner. Sometimes you will meet people who design and manufacture opal jewelry in their stores. Many business owners have their own opal mines, and their families have been working with opals for two or three generations.

Throughout Lightning Ridge’s opal mining history of more than a hundred years, the opal miners gradually developed their own trade standards. Specifically designed for black opal, the evaluation criteria of traits like brightness and quality of play-of-color are well accepted.

EYE-CATCHING RESEARCH

Lightning Ridge is the only place in New South Wales where opalized fossils have been unearthed. From gigantic dinosaur bones to microscopic tissues, opalization transformed these organic objects into precious gems. These opal fossils are not only valuable but also ideal for biological research. Many are perfect 3-D replicas of the once-living organisms. The transparency of the fossils allows scientists to see through them without breaking them. This is a big advantage for study compared to non-opalized fossils.

In Lightning Ridge we met a paleontologist, Elizabeth, and her students, who are studying opalized fossils. Many scientists from around the world visit Lightning Ridge to collect and study these samples. In some cases the biological and paleontological studies benefit the study of precious opal formation as well. With many years’ efforts, people have become more and more educated about these fossils. Opal miners are very mindful of them during the mining process. Fossil digging is especially fascinating for collectors and schoolchildren. An on-site class given by a paleontologist can plant an idea in young minds that can change their lives.

PRESERVING THE CULTURE

We met opal miners, cutters, dealers, and researchers in Lightning Ridge. One thing they all have in common is the belief they hold in opal. The sporadic distribution of opal in the deposit makes it hard to find; therefore the miners can sometimes have no valuable production for years. But most of the miners still choose to stay and keep mining. Most people in Lightning Ridge have multiple roles—as miners, dealers, and designers. Some miners are from overseas. At first they were visitors, but then they were stung by the opal bug and never left.

Today people from all over the world travel to Lightning Ridge to see precious opal and experience the outback lifestyle. A unique Australian Opal Centre is in development to highlight the stone and Australia’s opal mining culture. This project has drawn together opal miners, dealers, and researchers. It will become a national monument to pass the natural and cultural heritage to future generations.

Dr. Tao Hsu is technical editor of Gems & Gemology; Andrew Lucas is manager of field gemology for education at GIA Carlsbad; Vincent Pardieu is senior manager of field gemology at GIA Bangkok.

DISCLAIMER

GIA staff often visit mines, manufacturers, retailers and others in the gem and jewelry industry for research purposes and to gain insight into the marketplace. GIA appreciates the access and information provided during these visits. These visits and any resulting articles or publications should not be taken or used as an endorsement.

The authors would love to thank Terry Coldham for setting up their visit to Lightning Ridge. Warm thanks also go to the hosts at Lightning Ridge for such a nice experience.