Mogok Expedition Series, Part 1: The Valley of Rubies

March 20, 2014

Vincent Pardieu, senior manager of field gemology at GIA's Bangkok lab, has traveled extensively to Mogok in the past. For foreigners, travel to Mogok had been next to impossible over the last decade, but the Myanmar government recently loosened restrictions, and Vincent visited there in the latter part of 2013. At year’s end, Vincent invited Andrew Lucas, manager of field gemology for GIA education, to travel to Mogok with him. Andrew had been to Myanmar three times before but never to Mogok, as it had always been off limits. The 2013 and 2014 trips were the first visits to Mogok by GIA gemologists in over a decade, and the first time GIA education had someone on the ground in the area.

The authors left Bangkok on December 28, arriving in Mogok the same day. Vincent’s mission was to collect gemstone samples for the lab’s origin-of-gemstones research and to document the industry. Andrew was there to document the industry for GIA education. The expedition to a legendary gemstone source that many believe is unequalled had begun.

Top-quality Burmese rubies are the standard by which the world's production is judged. A record selling price for ruby was set at Christie's in St. Moritz on February 15, 2009, when an 8.62 carat cushion-shaped ruby realized a price of $425,000 per carat. This record-breaking gemstone was termed the desired "pigeon's blood" red used for highly sought rubies from Myanmar. Photo courtesy of Christie's.

Myanmar

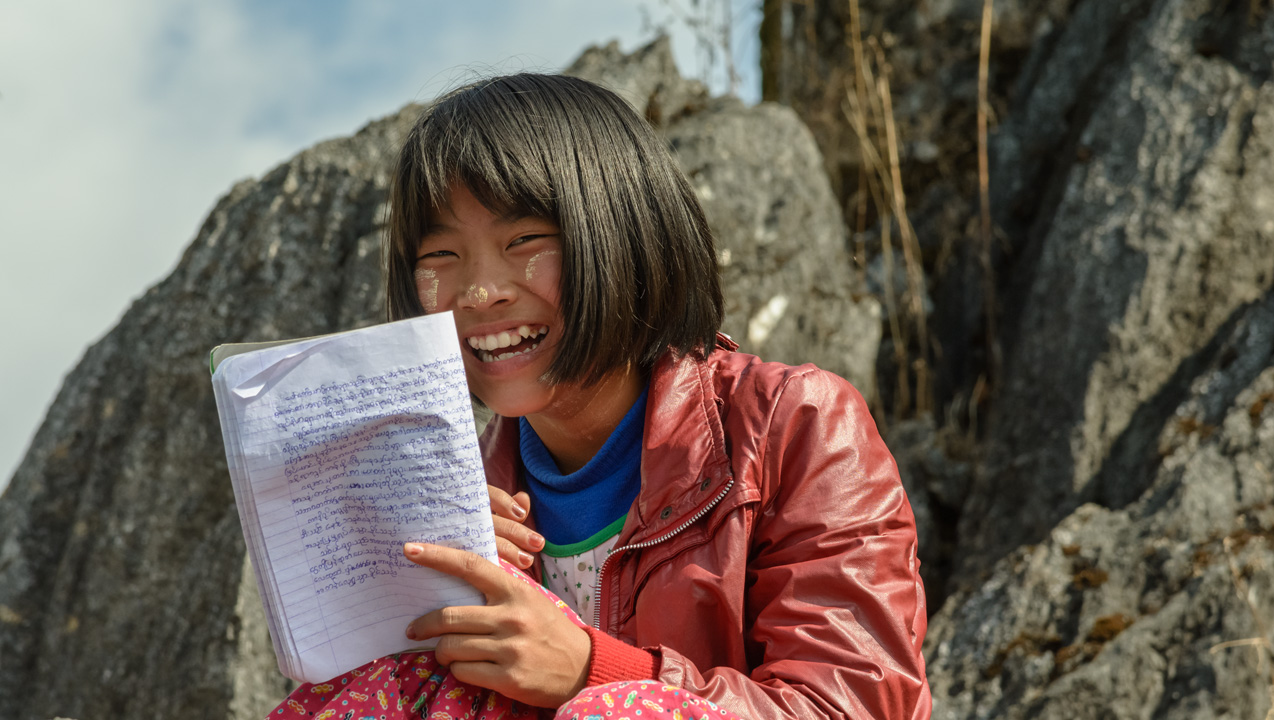

Myanmar is an amazing country with an incredibly diverse population. The country borders China, India, Thailand, Laos, and Bangladesh. It also reaches the shores of the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal. The country is home to approximately 60 million inhabitants, comprising numerous ethnicities and dialects. The government recognizes 135 ethnic groups, with the Burmese as the majority.The Mogok area borders the Shan State, which was settled about 1500 years ago. Today, the area hosts numerous ethnic groups. Besides the Burmese and Shan, other important ethnicities in Mogok include the Lissu and the Gurkha, the latter of whom are of Nepalese descent.

This Lissu woman is attending the morning gem market. Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

On this trip, we spent almost all our time in Mogok, focusing on gemstones. The authors had previously visited some of the country’s amazing cultural sights, such as the Shwedagon Pagoda on top of Singuttara Hill in Yangon. Gilded with gold plates, it provides one of the world’s most intense sightseeing experiences.

The Shwedagon Pagoda is an amazing sight. In addition to being covered in gold, the

upper areas contain thousands of gemstones, with a 76-carat diamond orb at the top.

Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

Bagan is one of the most inspiring areas in the world. Located on the banks of the Irrawaddy River, it has the world’s largest and densest concentration of Buddhist temples, pagodas, stupas, and other ruins. Bagan thrived from the 10th-13th centuries. At one time, the area might have had 13,000 temples and stupas. Today, those that remain have a romantic look, weathered by wind and erosion.upper areas contain thousands of gemstones, with a 76-carat diamond orb at the top.

Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

One of the best ways to get to Bagan is by taking a boat from Mandalay. This takes the better part of a day, but provides stunning views of temples along the river banks, with nomadic fishermen and villages devoted to making pottery. Also in the Bagan area are workshops where you can observe expert craftsmen creating all types of lacquerware.

Anyone interested in history, architecture, ruins, or a romantic, exotic location will be captivated by Bagan. Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

Buddhism’s influence is felt throughout Myanmar in its temples and pagodas and in the ever-present monks, who are often seen walking barefoot. While all the major religions are represented in Myanmar, the majority of the population—an estimated 89 percent—are practicing Buddhists.

Monks in red robes are seen throughout Myanmar. Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

At the start of our trip, the authors flew into Mandalay, the second largest city in Myanmar, the economic center of Upper Burma, and the country's last royal capital. It is also home to a thriving jade market, where vendors sell rough jadeite, and fashion and sell finished jadeite and jadeite-set jewelry. There are local dealers, foreign dealers, and tourists, all making their way through the market’s crowded lanes. Restaurants are busy serving customers and workshops are busy fashioning jadeite. It is a noisy place, with deals being made, cooking pots being handled, and jadeite being sawn, carved, and polished.

The jadeite market in Mandalay is a hustling environment with plenty of dealing in, and fashioning of, jadeite. Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

Mogok

From Mandalay, we traveled by van to Mogok with our guide. Jordan is his nickname, inspired by his exceptional height—especially for the Burmese—which inspires comparisons to Michael Jordan.

This amazing necklace, known as the Fai Dee Red Magic, is composed of untreated rubies from both Mogok and Monghsu, Myanmar. Photo courtesy of Fai Dee.

The trip to Mogok is much easier today than it was in the past. There are two paved roads reaching Mogok. The first was constructed in the early 1990s and takes you from Mandalay to Mogok in about six hours. The other road was finished fairly recently and allows you to bypass the drive through Mandalay to arrive a couple of hours earlier.Mogok is about 200 km northeast of Mandalay. It is part of the Kathe district of the Mandalay region, in an area often referred to as Upper Burma. The famous gem-producing area called the Mogok Stone Tract is actually made up of several valleys and their towns. The main ones are Mogok and Kyatpyin, but gems are also found in the valleys surrounding the villages of Bernardymo, Chaung Gyi, and Kyauk Pya That; they are also produced in the Kabaing and Kin valleys. Mogok has approximately 300,000 residents and Kyatpyin around 250,000.

Besides ruby, inhabitants also mine sapphire and spinel, along with commercial quantities of other gems, including apatite, scapolite, moonstone, zircon, garnet, iolite, and amethyst. The Tract is also home to rare stones such as painite, hibbonite, and poudretteite, which are found only in Mogok and a few other gem localities. While in the region, the authors visited a lapis lazuli mine at Oo Saung Thaung Mountain. Peridot is mined at Pyaung Gaung in the Bernardmyo area, where phot bought samples from miners.

Browse through this gallery and see the beauty and mystery of Mogok Valley.

Mogok History

In 1915, G.F. Kunz reported hearing a legend about how rubies originated in Mogok. The legend goes that around 2,000 years ago a serpent laid three eggs. The first egg bore the King of Bagan, the second egg bore an Emperor of China, and from the third egg came the rubies found in the ruby mines of Mogok.References to rubies and Burma have been found dating to the sixth century, during the Shan Dynasty. The ruby mines in Mogok were taken over from the Shan by the king of Burma in 1597. Any rubies over a certain size and weight had to be given to the king. It’s said that some larger stones were broken up so they could be sold rather than turned over. This is illustrated by the legend of Daw Nan Kyi.

According to the legend, a miner named Nga Mauk found an amazing ruby. Instead of giving the entire stone to the king, he broke it in half and gave half to the king, for which he was rewarded handsomely. He sold the other half to a Chinese merchant. Later, a Chinese prince requesting protection from the king presented the ruby as a gift to his court. Upon examination, the king felt that something about it looked familiar. When he compared the newly gifted ruby to the one the miner had presented, he saw that they fit together perfectly and realized he had been cheated. The king had the miner and his family burned alive. His wife, Daw Nan Kyi, witnessed this from a hill where she was collecting wood. She then died from a broken heart—broken in half like the ruby.

This is the view looking down Daw Nan Kyi Hill into the town of Kyatpyin. According to

legend, Daw Nan Kyi looked upon a similar view as she watched her family burned alive.

Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

The story of the Nga Mauk ruby does not end there. In the 1870s, during the reign of King Mindon (1853-1878), the French and the English were building colonial empires in Asia. A representative of the French visited the Burmese king and asked him how much he would ask to let some French companies mine in Mogok. The Burmese king then showed the Nga Mauk ruby to the Frenchman, asking him how much he would estimate its value to be. The Frenchman, who had never seen such a beautiful gem, said that it would be impossible to assign a value to such an exceptional gem. The Burmese King replied: If you cannot give me an estimate for that stone, how do you expect me to give you an estimate for the mine that produced it? The Frenchman was speechless and departed. Later, the British learned of the French interest in Mogok and Upper Burma, and feared that the French would take over the region and control access to China. Backed by a consortium of London-based gem merchants, they planned an invasion of Burma with one of its main objectives being control of Mogok and its ruby mines.legend, Daw Nan Kyi looked upon a similar view as she watched her family burned alive.

Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

A Mogok made gem painting shows King Mindon presenting the Nga Mauk Ruby to a Frenchman around 1870. Photo by Vincent Pardieu, ©GIA.

In 1886, the British succeeded in taking over Upper Burma. By 1889, they had formed Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. With tremendous interest in the company stock, the company received a series of leases, and was generally profitable until World War I. They introduced water cannons, washing plants, and other mechanized mining methods, and actually moved the town of Mogok into alluvial mining. The company did much to promote Burmese rubies in Europe and around the world. There were numerous operational problems, however, including flooding and theft. Also, the introduction of synthetic ruby caused widespread fear and plummeting prices in the marketplace. These problems finally led the company to abandon the mines in 1931.In the 1950s, French writer and traveler Joseph Kessel visited the mines and was inspired to write the novel, Mogok, the Valley of Rubies. This increased public recognition of Mogok as the homeland of the finest rubies in the world, especially among the French. After Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. departed the region, local mining went back to its former small-scale methods. Although not as productive as large-scale production, they proved to be more cost-effective and sustainable. When the government nationalized the mines in 1969, smuggling became rampant.

By 1990, mining regulations eased, allowing joint ventures. During the authors’ visits to the mining areas, we found numerous joint ventures between private companies and the government, as well as sole private ventures and foreign investment in mines.

Mogok mining activity includes both private and joint-venture operations. Photo by

Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

Photo by Andy Lucas, ©GIA.

The Geology

To view the topography of the Mogok Stone Tract is to witness a true geological spectacle. It is one of the most interesting and diverse gemstone environments in the world, with a wide range of geological events happening in the area.Among the most striking visuals of the geological environment are the impressive marble pinnacles that are blackened from weathering. These formations are visible throughout the stone tract and can vary tremendously in size. Once the black, weathered surface is removed, the white marble becomes visible. One of the largest of these outcroppings is the one that the temple Kyauk Pyat That sits upon. It is truly amazing to see these temple structures sitting on outcrops of rock called karsts, like something out of the science fiction movie Avatar.

Open this gallery and learn about marble pinnacles and their significance to Mogok’s terrain and ruby mines.

The karsts result from the weathering of the marble. This weathering process also plays a part in mining at Mogok. Since marble is an intricate component of much of ruby and spinel formation, as well as its host rock, the gems are weathered and transported along with the marble. The gems are then concentrated in gravels that the Burmese call byon. These gem-rich gravels are highly important to economically viable mining. The authors have seen similar karsts in other locations, like the ruby-producing region of Luc Yen, Vietnam, where they are mostly covered by jungle. The impact on the viewer of these impressive outcrops in Mogok, however, is hard to equal.Ruby and spinel are formed primarily by metamorphic events—the conditions that form mountain ranges—with rocks altered by both regional and local heat and pressure. One such giant earth event occurred when India collided with Asia. The tremendous force of that collision created the Himalaya Mountains and the geological conditions that allowed for the formation of many gemstones, including ruby, sapphire, and spinel.

This Burmese ruby necklace, scheduled for auction at the Hong Kong Sotheby's show on April 7th, 2014 is expected to yield USD $8.7million. Photo courtesy of Fai Dee.

Ruby and spinel are commonly found in marble. Deposits associated with the collision between Asia and India are found in several locations on all sides of the Himalayan range: In Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan on the western side, in Nepal in the center, and in Vietnam and Myanmar on the eastern side. Because their geological origins are very similar, the stones from these deposits share many characteristics. This creates some fascinating challenges for gemologists working on origin determination.Skeletons of creatures from ancient ocean-associated, lagoon-type environments contributed calcium and carbon to the sediments, forming limestone that was very impure and rich in clay and organic matter. Heat and pressure converted the limestone to marble during the geologically catastrophic collision of India and Asia. During that metamorphic event, fluids rich in salt and carbon dioxide, resulting from evaporation, were also put in motion. The interaction between these fluids and the marble deposits caused reactions that freed elements like aluminum, chromium, magnesium, and vanadium. The combinations crystallized as spinels when magnesium was present; otherwise, rubies formed in the cavities that resulted from the dissolution of the salt from the evaporite beds.

The actual formation process is very complex, but simply stated, the rubies associated with marble-type deposits along the Himalayan chain originated from the remains of some of the first life forms that existed on earth hundreds of millions of years ago. Blue sapphire, on the other hand, is associated with igneous intrusions, and forms from a relationship between the igneous intrusions and the metamorphic rock, called metasomatism.

These geological events illustrate the great complexity and combination of circumstances necessary for gemstone formation. The chance that a fine ruby or other gemstone will form is also dependent on slow cooling and enough time and space for the crystal to grow—rare combinations indeed.

About the Authors

Vincent Pardieu is senior manager of field gemology for the GIA laboratory; Andrew Lucas is manager of field gemology for GIA education.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following for all their help: Jordan, a very good friend who was our driver, guide, and translator; Jean Yves Branchard from Ananda Travels in Yangon, Myanmar, who helped us with permits and logistics; and, of course, the people of Mogok, who welcomed us and shared with us their knowledge and friendship.